UCLA Research Shows Cold Plasma Can Kill Coronavirus on Common Surfaces in Seconds

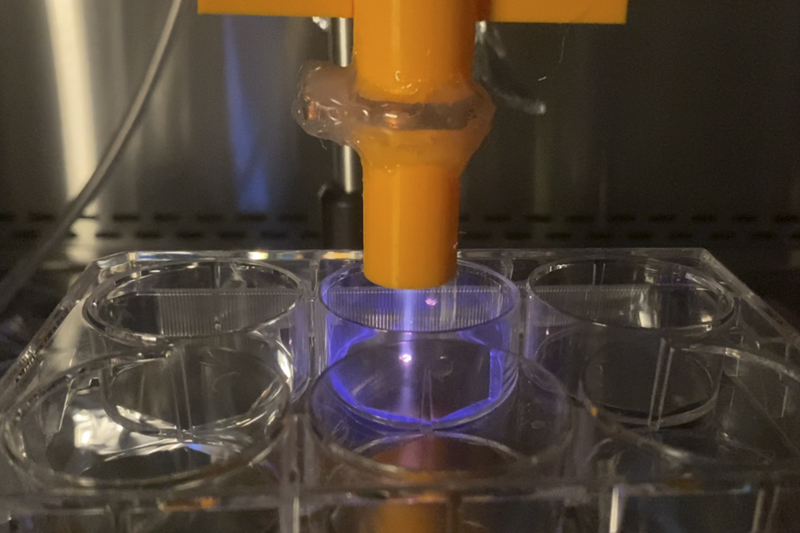

Cold atmospheric plasma device treating metal samples in a six-well plate. The glowing is due to the presence of excited air molecules, not to higher temperatures.

A study detailing the research, which was published this month in the journal Physics of Fluids, is the first time cold plasma has been shown to effectively and quickly disinfect surfaces contaminated with the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19.

The novel coronavirus can remain infectious for tens of hours on surfaces so the advance is a major breakthrough that may help slow the spread of virus.

“This is a really exciting result, showing the potential of cold atmospheric plasma as a safe and effective way to fight transmission of the virus by killing it on a wide range of surfaces,” said study leader Richard Wirz, professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at the UCLA Samueli School of Engineering.

Plasma, not to be confused with blood plasma, is an electrically charged gas known as the fourth state of matter (solid, liquid and gas being the others), with electrons and charged ions accounting for its main makeup.

The researchers created the plasma by subjecting air and argon gas — a common, non-toxic gas — to a strong electric field across electrodes inside a spray jet built by a 3D printer. The resulting ionized, atmospheric cold plasma remains stable at room temperatures.

The team used the jet to spray plastic, metal, cardboard and leather surfaces laced with SARS-CoV-2 cultures. The jet ionized the surrounding air, turning it into cold atmospheric plasma and killing most of the virus after 30 seconds. The team saw similar results with cotton from facemasks. Leather from a basketball, football and baseball was included to test effectiveness in disinfecting sports equipment and to simulate the rough and wrinkled surface of skin.

Cold plasma has previously been shown in research studies to be effective in cancer treatment, wound healing, dental-instrument disinfection and other applications.

An important advantage of plasma is that it can be safely used on a variety of surfaces without damaging them, while treatments with chemicals and UV light cannot be used effectively on porous surfaces like cardboard and skin without damage.

Another advantage is an estimated lower cost for supplies compared to standard chemical sanitizers. The researchers are working with campus units at UCLA to further test the system.

“This eco-friendly, innovative technology could be implemented to prevent the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in hospitals, transportation and sports settings,” said study co-author Vaithi Arumugaswami, an associate professor of molecular and medical pharmacology at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA.

According to Wirz, cold plasma may even be a potential candidate, pending further study, to kill the coronavirus when it is airborne.

The study’s lead author is Zhitong Chen, a postdoctoral scholar in Wirz’s research group, which performs a wide range of plasma-based research, from propulsion to fusion materials.

UCLA staff research associate Gustavo Garcia, a member of Arumugaswami’s research group, is also an author on the paper.

The research was supported in part by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research, with additional support from the Geffen School of Medicine and the Broad Stem Cell Research Institute.

The researchers have also created a UCLA-based startup, uPlasma, to further explore the potential of the technology.