On a recent Saturday, under the hot desert sun 90 miles north of Los Angeles, 45 Aerospace Engineering students from UCLA gathered at the Reaction Research Society’s famed Mojave Test Area. Their challenge: achieve the highest apogee while launching and safely landing an unbroken egg in rockets they had built in class.

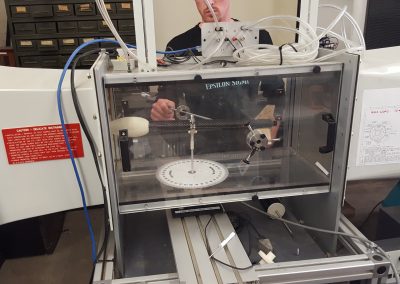

The students, divided into 10 teams of four to five students each, were part of a new capstone course that gives seniors design and build experience under “real-world” conditions. Classroom activities and lab work brought together the analytical tools, materials science, manufacturing techniques and testing methods commonly used in the aerospace industry.

Sam Dupas, aerodynamics engineer on the Starship Troopers team, will continue his education at UCLA in the fall as he pursues his master’s degree in Aerospace Engineering. Having gained experience in Computational Fluid Dynamics during an internship at Edwards Air Force Base with an eye toward an eventual career in aerospace, Dupas credits the class for helping him better understand the connection between design, analysis, and manufacturing.

“The most valuable thing I took away from MAE 157A was in doing our own fabrication,” he said. “It’s really easy to go on the computer and draw up some shapes, and draw up a design, and say ‘this looks great.’ When you actually have to take it into the machine shop, take a part on the lathe or the mill, and actually do that in person, it’s a lot harder than just following the directions on your paper.”

For Janelle Rogers, an Air Force ROTC member who plans to go into space operations and flight test engineering, the biggest aha moments came around the teamwork involved in projects of this scale.

“I was the design engineer on the team, but we were all communicating constantly,” Rogers said. “That taught me a lot about how that would be in industry. You have to know a little bit about every aspect but be really, really good at your own aspect.”

Assistant Professor Mitchell Spearrin, who built the class around his experience as a combustion devices development engineer at Aerojet Rocketdyne, wanted to make things as realistic as possible, with critical design and launch readiness reviews counting as part of students’ grades.

He also wanted to give students a sense that “real engineering problems are messy.”

“Real problems typically require the application of numerical models that provide approximate solutions and testing of prototypes or system components that involve some trial and error,” Spearrin said.

Working through those issues can be challenging, but ultimately that is where the rewards are, according to Spearrin, who also wanted to make sure his students had fun in the process.

“If you don’t get excited when watching something you’ve designed and built launch into the sky at 400 miles per hour,” he said, “you probably weren’t meant to be an aerospace engineer!”

For more information on the class and the rocket launch competition, read the full report on the Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering Web page.