Technobabble translation: In 1969, a UCLA team sent the very first message ever on the Internet — the proclamation “LO,” the first two letters of “LOGIN” cut short by a computer crash — to colleagues at the Stanford Research Institute in Menlo Park, Calif.

To commemorate the historic transmission, UCLA has established the Leonard Kleinrock Internet Heritage Site and Archive, which opened to the public on Saturday. The museum is the brainchild of Brad Fidler, a UCLA doctoral candidate in the history of science, who was surprised to find that no memorial — not even a wall plaque — was to be found in 3420 Boelter Hall, the computer lab where Distinguished Professor of Computer Science Leonard Kleinrock led a team of faculty and graduate students in making Internet history.

To commemorate the historic transmission, UCLA has established the Leonard Kleinrock Internet Heritage Site and Archive, which opened to the public on Saturday. The museum is the brainchild of Brad Fidler, a UCLA doctoral candidate in the history of science, who was surprised to find that no memorial — not even a wall plaque — was to be found in 3420 Boelter Hall, the computer lab where Distinguished Professor of Computer Science Leonard Kleinrock led a team of faculty and graduate students in making Internet history.

“A lot of the initial inspiration came from the fact that we have this historical site at UCLA,” said Fidler, adding that, considering the Internet’s profound influence around the world, surprisingly little research been done on its history.

Fidler contacted Kleinrock and others who worked in the Boelter Hall lab in the ’60s and ’70s, telling them about his plans and asking for archival materials. Kleinrock was the first to donate his papers to the project, but Fidler noted that everyone he contacted has been very helpful. Working his way through the documents and photos they contributed, as well as by conducting interviews, he was able to construct a mental image of the original lab setup and working environment.

“The process of setting (the museum) up has been very fun and interesting,” Fidler said, “whether it’s been trying to figure out the exact location of where everything was, or looking for documents.”

Fidler has also been in contact with people outside of UCLA who played part in the early days of the Internet. These included people who worked at ARPA (now DARPA, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency), which funded the development of the Internet, originally known as ARPANET.

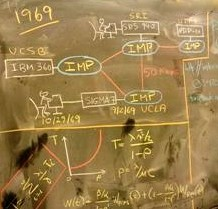

In designing the museum, Fidler set out to make the space appear much as it did four decades ago. At the same time, he wanted to incorporate information about the work that was done there. Fidler filled the room with replicas of mainframe computers and reproductions of a variety of documents — perhaps most significantly, the hand-written IMP Log, IMP being the acronym for the Interface Message Processor, the refrigerator-size machine that sent the groundbreaking communication. Museum visitors can page through the documents, which are informally arranged atop desks and machines as if Kleinrock’s team had just put them down. Additional historical materials and short history lessons are offered via blackboards and slides.

“It’s kind of an immersive environment,” Fidler said. “Nothing to break the illusion.”

The illusion came to life last Saturday during a grand opening party hosted by Fidler. Guests included Kleinrock and faculty colleagues, students and Internet history enthusiasts from around the city. The ’60s-themed party featured music and even a few guests sporting the tie-dyed look of that era.

With the museum now in place, Fidler is moving on to new initiatives. First — and perhaps most obvious given the subject of the museum — he’s working to create a digital archive of all the historic documents on display. He’s also planning a speaker series in which lecturers will discuss not just the early days of the Internet, but its broader social, cultural and historical significance.

For now, the Leonard Kleinrock Internet Heritage Site and Archive is open to the public on Thursday afternoons from 4 to 7, but Fidler said this this may change, depending on how much interest there is. The museum is also available by appointment to accommodate groups for events and tours. And next summer, it will be incorporated into a new undergraduate course taught by Fidler on the history of the Internet.

For now, the Leonard Kleinrock Internet Heritage Site and Archive is open to the public on Thursday afternoons from 4 to 7, but Fidler said this this may change, depending on how much interest there is. The museum is also available by appointment to accommodate groups for events and tours. And next summer, it will be incorporated into a new undergraduate course taught by Fidler on the history of the Internet.

The archive, Fidler said, serves as a reminder that the Internet — today a massive network that connects us with countless others around the globe — started out as “people-made” project on a very small scale. The number of people online that day in 1969? Three.

Main Image: Kleinrock with the Interface Message Processor his team used to send a message all the way to Menlo Park, Calif. Inset Images: Leonard Kleinrock, Distinguished Professor of Computer Science, in the Boelter Hall lab where history was made. A blackboard shows the strategy UCLA computer scientists laid out in 1969 for sending the first-ever message across the Internet.