UCLA Engineers Receive NSF Grant to Research Interaction-Powered Smart Environment Automation

Jacob Sayono/Human-Centered Computing & Intelligent Sensing Lab (HiLab) at UCLA

Everyday devices outfitted with e-UCLA-developed mini kinetic energy-recovery systems “MiniKers” to automate operation

UCLA Samueli Newsroom

There is a good chance most people enter a grocery store through an automatic door without a second thought. For individuals with disabilities, however, the option is not only for convenience, it is a necessity.

Automation not only boosts efficiency but also creates environments that can be equally accessible. Many objects, however, require users with enough dexterity, motor strength and often the use of both hands to operate. These requirements can be challenging for someone with motor impairments or other disabilities.

What if all doors, drawers, windows and other objects could be automated and without using an external power source as currently required?

“We turned our focus to people — a rich source of kinetic energy,” said Yang Zhang, an assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering at the UCLA Samueli School of Engineering. “Human environments, especially public spaces, are often occupied by users with different abilities, and their interactions can be turned into power that can then automate everyday objects for people who have limited mobility.”

A research team led by Zhang recently published its initial findings in Proceedings of the Association for Computing Machinery on Interactive, Mobile, Wearable and Ubiquitous Technologies. The researchers have received a three-year, $550,000 grant from the National Science Foundation to continue their work in collaboration with colleagues at the Georgia Institute of Technology, with a focus on creating tools to develop more efficient systems powered by human interactions.

“Wiring everything, or constantly replacing batteries are difficult power solutions to scale up,” said Zhang, who leads the Human-Centered Computing & Intelligent Sensing Lab at UCLA. “We suspect that’s why we have only seen the success of automation on a few objects while the majority of everyday objects remain human-operated.”

Other potential and sustainable energy sources, such as solar and wind energy, cannot readily scale down to the parameters required for everyday automation, according to Zhang. Instead, Zhang and his colleagues are spearheading innovative research on automating projects by using energy harvested from routine actions taken by individuals.

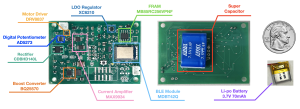

The system design includes a small motor that harvests energy from applied force, an electrochemical device called supercapacitor to store energy, and a circuit board that controls the system and connects via Bluetooth to a voice-activated smartphone app. The app will require specific user commands and can help safeguard young children from accidentally triggering a device without adult supervision.

“We not only used the motor for energy harvesting and actuation, but we also managed to repurpose it as a sensor, using the induced interaction-powered current as a signal to infer a specific user activity,” said UCLA graduate student and lead researcher on the project Xiaoying Yang.

The research team designed, built and tested variations of these tiny kinetic energy-recovery systems, or MiniKers, that opened and closed sliding doors, drawers, a small refrigerator door, a toilet lid, a rubbish bin lid, window blinds and curtains.

Using off-the-shelf and custom 3D-printed parts, one MiniKers-outfitted device costs about $60 per design. The researchers said such systems could be much more affordable if manufactured in bulk.

“Ultimately, this could be something you could pick up at a home-improvement store and install yourself,” Yang said.

Other authors on the study are UCLA undergraduate students Jacob Sayono and Jess Xu, as well as graduate student Jiahao “Nick” Li. Josiah Hester, an associate professor of computing at Georgia Tech, also collaborated on the project. The researchers have made their hardware, software and 3D-printing files available on GitHub.